The island of Nauru.

Australia’s determined efforts to keep sick refugees away from its shores have been stymied by patients who repeatedly refuse to fly to Taiwan for medical treatment, documents obtained by BuzzFeed News reveal.

Under a deal struck in 2017, Taiwan agreed to temporarily take in sick refugees and asylum seekers detained by Australia on the tiny Pacific Island nation of Nauru when they required complex medical care.

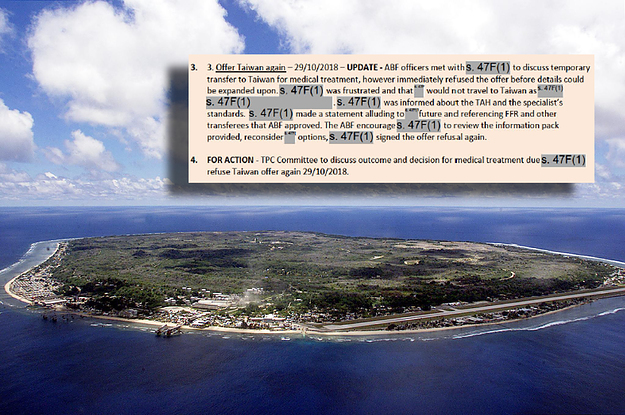

The secretive deal was an expensive but apparently neat solution to the dilemma created by Australia’s hardline immigration policies. Asylum seekers who arrived by boat following 2013 were sent to island detention on Nauru and in Papua New Guinea, and were unable to settle in Australia.

But as detainee health deteriorated and public outcry rose, a second policy mandated these people also could not travel to Australia for medical treatment unless their condition signalled death or significant, permanent disability, and they could not be treated elsewhere.

A significant number of cases did not meet that extreme threshold, but could not be treated with the expertise or equipment available in the island camps. Taiwan, with its high quality tertiary care, stepped in to fill the breach.

Since then, a big problem has arisen — many refugees don’t want to go. The deal has seen the government repeatedly encouraging refugees to travel thousands of kilometres to Taiwan for medical treatment, only to be met with refusals in half of all cases.

Redacted minutes of the Transitory Persons Committee — a secretive taskforce within the Department of Home Affairs — reveal a pattern of repeated approaches to patients about Taiwan, even after they have refused to go. BuzzFeed News obtained the minutes under freedom of information laws.

Minutes from Aug. 8, 2018.

At numerous meetings from mid-2018 until the committee apparently dissolved in March 2019, the group resolved to go back to patients who refused the Taiwan option and simply try again.

In one case, debated in November 2018, doctors had recommended medical transfer to Australia or Taiwan within a month. The patient had “refused multiple times” to go to Taiwan. The committee resolved to re-offer Taiwan, specifying that reasons should be recorded if the patient again declined.

In another case the following month, a patient had expressed “concerns” about Taiwan and refused to go. The committee agreed to double down on its efforts to get them on a plane. It asked for a report clarifying the patient’s concerns and confirming the patient had been adequately informed about the risks of not receiving treatment. The committee specified that the patient should be accompanied by an interpreter, ideally somebody who could be introduced to them on Nauru at or before the time the offer was discussed again.

A number of refugees held on Nauru told BuzzFeed News that the treatment they received was not satisfactory and did not resolve their medical problems.

One said he was not given access to an interpreter in Taiwan, where he and his son stayed for longer than their treatment required so that they could be sent back to Nauru in a batch of four.

The man, who spent four months on Nauru in early 2019, said people on Nauru were declining Taiwan transfers as they thought it would be a waste of time and money, because they had seen others return with ongoing health problems, or even exacerbated conditions.

“The group of people that saw this lot come back with incomplete work decided not to go any more,” he said. “They said, ‘Well, what a waste’. There’s a popular belief that if you refuse to go to Taiwan, eventually they have to take you down to Australia for treatment.”

Thirty-three people had gone to Taiwan for treatment by the end of July 2019. Another 33 had refused to go, according to figures provided by the home affairs department to politicians.

The memorandum of understanding between Australia and Taiwan specifies that patients have to give written and informed consent to receive medical treatment in Taiwan before being sent there.

A plan lands at Taipei’s airport.

The taskforce also debated whether the government discharged its duty of care in simply offering a Taiwan transfer, even if a patient refused to go and their health problems persisted.

On July 23, 2018 the committee discussed the “time critical” case of a person on Nauru who Taiwan had agreed to take. The committee discussed that the government “may have a chance” of avoiding a court order to bring the person to Australia, if they could show that a transfer to Taiwan was logistically possible and could be done just as fast.

A month earlier, in the case of another patient who had refused to go to Taiwan, the committee “discussed at what point has the Department fully discharged its duty of care and any residual duty of care”. They resolved to prepare another offer to Taiwan.

Throughout 2018 Federal Court judges had ordered refugees be transferred from offshore detention to Australia or somewhere with similar quality medical care, based on Australia’s duty of care to them.

The committee also grappled with how refusals affected the application of the hardline policy.

The committee’s chair, first assistant secretary Elizabeth Hampton, argued in a June 2018 meeting that if Taiwan was willing to accept a patient who refused to go, transfer to a third country was still technically available, “so any other decision [like transfer to Australia] goes against the policy”.

Another first assistant secretary, David Nockels, suggested that to read the policy anything but “verbatim” could open the door to all cases to transfer to Australia, noting that if they allowed someone to come to Australia in those circumstances, it would “null and void Taiwan and any other third country option and undermine the policy”.

The committee noted that the policy was ambiguous and resolved to discuss it with the department’s acting secretary. They also discussed whether there was any “room for compassion” in the policy. The minutes do not record how those debates were resolved.

The Taiwan deal was signed in September 2017, and the first transfers took place in January the following year.

The medevac law, in force since March 2019, overrode the government’s hardline policy by giving doctors greater say over medical transfers to Australia.

The government is fighting to wind back medevac and return to the old system, leaving Taiwan as an important plank of the healthcare regime in offshore detention.

The Department of Home Affairs did not respond to a request for comment.